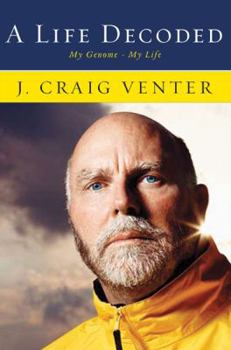

A Life Decoded: My Genome: My Life

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The triumphant true story of the man who achieved one of the greatest feats of our era—the mapping of the human genome Growing up in California, Craig Venter didn’t appear to have much of a future. An unremarkable student, he nearly flunked out of high school. After being drafted into the army, he enlisted in the navy and went to Vietnam, where the life and death struggles he encountered as a medic piqued his interest in science and medicine. After pursuing his advanced degrees, Venter quickly established himself as a brilliant and outspoken scientist. In 1984 he joined the National Institutes of Health, where he introduced novel techniques for rapid gene discovery, and left in 1991 to form his own nonprofit genomics research center, where he sequenced the first genome in history in 1995. In 1998 he announced that he would successfully sequence the human genome years earlier, and for far less money, than the government-sponsored Human Genome Project would— a prediction he kept in 2001. A Life Decoded is the triumphant story of one of the most fascinating and controversial figures in science today. In his riveting and inspiring account Venter tells of the unparalleled drama of the quest for the human genome, a tale that involves as much politics (personal and political) as science. He also reveals how he went on to be the first to read and interpret his own genome and what it will mean for all of us to do the same. He describes his recent sailing expedition to sequence microbial life in the ocean, as well as his groundbreaking attempt to create synthetic life. Here is one of the key scientific chronicles of our lifetime, as told by the man who beat the odds to make it happen.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0670063584

ISBN13:9780670063581

Release Date:October 2007

Publisher:Viking Books

Length:390 Pages

Weight:1.54 lbs.

Dimensions:1.4" x 6.6" x 9.6"

Age Range:18 years and up

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher