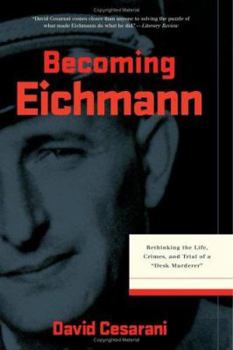

Becoming Eichmann: Rethinking the Life, Crimes, and Trial of a Desk Murderer

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In charge of the logistical apparatus of mass deportation and extinction, Adolf Eichmann was at the center of the Nazi genocide against the Jews. He was personally responsible for transporting over two million Jews to their deaths in Auschwitz-Birkenau and other death camps. This is the first account of Eichmann's life to appear since the aftermath of his famous trial in 1961 and his subsequent execution in Jerusalem a year later. It reveals that the depiction of Eichmann as a loser who drifted into the ranks of the SS is a fabrication that conceals Eichmann's considerable abilities and his early political development. Drawing on recently unearthed documents, David Cesarani shows how Eichmann became the Reich's "expert" on Jewish matters and reveals his initially cordial working relationship with Zionist Jews in Germany, despite his intense anti-Semitism. Cesarani explains how the massive ethnic cleansing Eichmann conducted in Poland in 1939-40 was the crucial bridge to his later role in the mass deportation of the Jews. And Cesarani argues controversially that Eichmann was not necessarily predisposed to mass murder, exploring the remarkable, largely unknown period in Eichmann's early career when he first learned how to become an administrator of genocide. This challenging work deepens our understanding of Adolf Eichmann and offers fresh insights both into the operation of the Final Solution and the making of its most notorious perpetrator.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0306814765

ISBN13:9780306814761

Release Date:April 2006

Publisher:Da Capo Press

Length:458 Pages

Weight:1.59 lbs.

Dimensions:1.6" x 6.3" x 9.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

THE MODERN AGE'S MOST SUCCESSFUL MASS MURDERER

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Cesarani's book is (1) an attempt to come to grips with an enigma, a seemingly bloodless bureaucrat who was responsible for the murder of more than five million people in WWII and (2) a rebuttal and revision of the highly influential thesis of Hannah Arendt that Eichmann was the archetype of a new kind of murderer, a pencil pusher who sent people to their death at the behest of a monolithic state machine (Eichmann in Jerusalem, 1963). (Stanley Milgram's controversial experiments on obedience to authority (also 1963?) buttressed to Arendt's conclusion. Cesarani presents a much more nuanced view: Eichmann wasn't an unhappy child, wasn't persecuted by or identified with Jews, but he did imbibe the deep anti-Semitism of those around him. His entry into the Party and his drive to succeed, a perverted careerism as it were, eventually blunted all moral sensibilities and he became a moral monster. Quotations from Eichmann and others in this book are telling -and chilling. Of his operations in Hungary, Eichmann claimed that "On principle, I never went to look at anything unless I was ordered to." Eichmann's superior Heinrich Muller stated: "If we had fifty Eichmanns we would have won the war automatically." Eichmann said that when he finally knew the war was lost, "I sensed I would have to live a leaderless, difficult individual life, I would receive no directives from anybody, no orders and commands would any longer be issued to me, no pertinent ordinances would be there to consult -in brief, a life never known before lay ahead of me." When Eichmann in hiding in Argentina, a neighbor reminisced that he was very good with forms; whenever his mother had official forms to fill out, she would asked Eichmann to help because "he understood how they all worked." Eichmann's son Klaus talked Quick magazine in 1966 about their life in hiding in Argentina: "We learned Spanish at high speed. Father ordered me to learn one hundred words a day, no more, no less. It had to be exactly one hundred words. Our father was very correct, everything had to be just so, everything had to be in exact order." When Eichmann was interrogated before he went on trial, he stated: "I have no regrets at all and I am not eating humble pie at all. ... I must tell you that ... my innermost being refuses to say that we did something wrong. No -I must tell you, in honesty, that if of the 10.3 million Jews shown by [the statistician] Korherr, as we now know, we had killed 10.3 million, then I would be satisfied. I would say, `All right. We have exterminated an enemy.'" One of his jailers observed that as a prisoner, Eichmann "behaved like a scared submissive slave whose one aim was to please his new masters." Denying any active role in the mass murder of Jews and other `defectives', Eichmann said: "Although there is no blood on my hands I shall certainly be convicted of complicity in murder." Of Eichmann's demeanor during his trial, Cesarani writes: "His studied indifference was a piece

Excellent revision of the Eichmann story

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

The problem with all books dealing with evil people is that they begin with the assumption of exceptionalism: that the mass murderer is an exception. The 20th Century, if not all recorded history, should have taught us that this is not so. The Mongols Ghengis Khan led in their slaughters were no more inherently evil than Eichmann or the Soviet executioner who won an award for shooting several thousand people in a few days. Cesarani does a good job of presenting Eichmann as an ordinary man seeking advancement and prestige within a society that saw nothing wrong with murdering millions. Hannah Arendt's characterization of Eichmann as a dim-wit was nothing but an intellectual's refusal to acknowledge that the Germans in their bloodlust were no different than the Soviets, Communist Chinese or other societies that considered murder and enslavement a normal part of the exercise of power. (It should be remembered that Stalin and Mao each murdered more of their own citizens than the total of all murdered by the Germans. Stalin and Mao also enslaved hundreds of millions more people than the Germans. These have always been inconvenient facts for left-leaning intellectuals to deal with, thus their propensity to attempt rendering the German experience as unique.) Cesarani traces every aspect of Eichmann's life, sometimes to the point of dullness. The ultimate story is that Eichmann wasn't any different than any of his peers in Germany, the Soviet Union or what would become Communist China. In Germany, it is estimated that about 500,000 people were at one time or another in the extermination of Jews and other groups, not counting their Ukrainian, Polish, French and other European helpers. Eichmann held an important position in this apparatus, organizing and administering much of the system that gathered and delivered Jewish victims to the place the Germans had designated for their cruel deaths. Cesarani successfully "humanizes" Eichmann as a man who could spend his work hours plotting the deliberate enslavement and murder of millions simply because they were Jewish and literally go home to be a typical husband and father. It is that part of Eichmann and nearly all the other state-sanctioned murderers like him through the ages that is so disturbing. To them, slaving and murder was an ordinary part of their lives. For many today, it still is: just look at the recent experience in the Balkans, the Sudan and elsewhere. The ultimate repugnancy of Eichmann is that he was the exception in that he was tried and hanged. Of the estimated 500,000 Germans who are estimated to have participated in the murder of the Jews, very few were punished. Most went on to live the normal lives their victims were denied. The same is true of the killers in the former Soviet Union, China and elsewhere in the 20th Century. Such crimes and the criminals who commit them are too easily forgotten. Cesarani is to be congratulated for once again reminding us that ordinary men and w

Excellent balanced review of a 'genocidaire'

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Studying the motivations of those who actively participated in the Holocaust and trying to understand them is no easy task. There have been many attempts to do so ranging from a simplistic 'they must have been monsters' view to 'they were victims of their circumstances'. But neither captures the true complexity of interacting causes of any one person's behaviour nor the slippery-slope aspect of increasing brutalisation through participation. Sadly for humanity's peace of mind, there is probably no simple explanation for why anyone actively participates in genocide - if there were we should have been able to prevent its regular reccurence since 1945. However, David Cesarani goes a long way to reaching the most balanced view I've yet read to date. The book assumes that you are reasonably familiar with the facts and chronology so a novice of the era would probably struggle to keep up with the narrative. Cesarani takes you through Eichmann's life until his kidnapping by Israeli agents in Argentina at a fair pace, occasionally skimming events that you might have wanted covered in greater detail. But this is not a book about what happened - it's looking at Eichmann the man, and so the author rightly (in my view) does not dwell on the untold misery and horror that he inflicted from afar (and witnessed on occasion at close quarters) on millions of innocent people. He then goes through his trial in Israel in great detail giving as much attention to the trial as to Eichmann himself. It becomes clear that the trial needed to serve the interests of the State just as much as the interests of Justice, but nevertheless, the verdict is no surprise to anyone except perhaps Eichmann himself. And here lies the clue to the real man within. Eichmann lived a life so full of self-delusion for so long that he found it impossible to separate the spark of real humanity left within his corrupted soul from all the conceited self-justifications, lies, propaganda and, ultimately, anti-semitism that had so taken over his life and his sense of Self. The book ends by assessing Eichmann's impact on history and the debate over the Nazi Final Solution. He takes time to argue against Hannah Arendt's views as expounded in her book of the trial (The Banality of Evil), claiming she was only interested in pushing her personal theory, and because of the huge publicity she achieved, how she warped the ongoing debate. This book certainly addresses this and puts Eichmann back into a more balanced, and in my view, more realistic place. Cesarani leaves you with a view that although Eichmann was made by his circumstances (he could never have become a genocidaire without Hitler's Nazi state), he was ultimately personally responsible for allowing himself to be sucked into the machinery of genocide. In other words, Eichmann started out as normal a person as you or I, but he chose the path he trod - and, quite rightly, his end was that reserved for a monster.

Painted the abduction of Eichmann in such cinematic detail..

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

I won't go into the full-on details of what this book entails, for I feel the other most capable reviewers plus the publisher's back cover copy of Mr. Cesarani's book do more than an adequate job. I thank Mr. Cesarani for painting a most cinematic-like picture of the Eichmann takedown in the Argentine. I relished every page and line of that chapter for the simple reason that the story we already knew the outcome of was narrated in such a hair-raising and chilling style. Narrative non-fiction is truly the word of the age. This was one of the better books I've read all year.

Almost everything you wanted to know about Eichmann......

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

But were afraid to ask. Well, almost everything. David Cesarani specializes in thoroughly researched biography (see his fulsome, almost too much so, book on Arthur Koestler) and here you find everything about Eichmann's background and career, except a definitive explanation of why he did what he did and was what he was. Here is a good refutation of Hannah Arendt's Eichmann who was just a dimwitted cog in the genocidal wheel of the Nazis. The real Eichmann freely made career choices which slowly but surely made him an effective executive participant in the murder of Europe's Jews during the Second World War. Was he a convinced anti-semite or only a career opportunist? Hard to say, but certainly the Austrian Protestant milieu in which he grew up contributed to his willingness to become a genocidal expert. He had none of the Austrian Catholic Schamperei which while negative about the Jews was never efficient enough to do more than create unpleasantness for them. Eichmann was more disciplined, more determined, and more effective. Like many other careerists in the Third Reich it was enough to know that enthusiasm and initiative in the war against the Jews would be rewarded by higher officials in tune with Hitler's ultimate desires and urges. There was nothing "banal" about Eichmann's activities or beliefs but he was not unusual either, one of hundreds of thousands of officials, teachers, clergy, military, and professionals who found the Hitler regime open to their expertise in the solving of problems. Eichmann was good at transportation problems and their solution, whether the commodity in question was grain, shoes, or living Jews. He knew how to get them to Riga or Minsk or Auschwitz where they would be shot or gassed in accorance with his instructions from Heydrich and Himmler. This is a book well worth reading and pondering. Perhaps not just anyone but certainly a rather large number of Americans could become Eichmanns under the right circumstances.