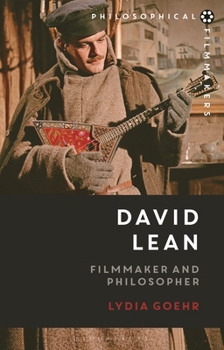

David Lean: Filmmaker and Philosopher

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

David Lean's extraordinary films work philosophically through the modern reproductive and transportive technologies of sight and sound: through trains, planes, ships, and automobiles, from one perspective, and through the modern technology of the radio and gramophone, from another.

Lean's musical motifs are known worldwide: Lara's theme in Zhivago; the Colonel Bogey March in Kwai; Estella's motif in Great Expectations; Rosy's motif in Ryan's Daughter; Lawrence's motif for his adventure in Arabia, and of course Rachmaninoff's pounding chords in Brief Encounter. When, however, Lean described his cutting of pictures as akin to how music flows through pictures, what sort of music or musicality had he in mind: a classical or popular music, or a way of using musical form to mix up the meaning and material of his films? Lydia Goehr's new book tracks the soundscape in Lean's films not only through the musical scores composed for the films, but also, and more, through the technology of radio and gramophone that, at the start of Lean's career, were becoming indispensable household items for the home. The book begins and ends with a motif running from the early more domestic films locally situated in the English home to the later more extensive epics of colony, commonwealth, and empire. The fidelity-infidelity relationship defined by marriage extends to the loyalty-betrayal relationship regarding countries of war and peace-after which this relationship is extended to the witty British manner of making film as a perfected and not so perfected symphonic work of a great cutter's art. Here, as few other books on Lean have emphasized, the influence of Noel Coward on Lean cannot be overestimated.Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1350429325

ISBN13:9781350429321

Release Date:July 2025

Publisher:Bloomsbury Academic

Length:272 Pages

Weight:1.00 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 6.1" x 9.2"

Customer Reviews

0 rating