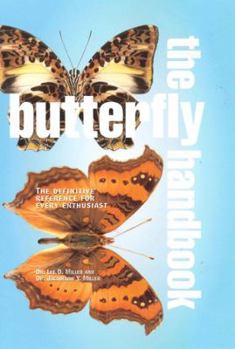

The Butterfly Handbook

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Each of the 500 species depicted here is illustrated with a full color close up picture showing its vibrant colors and intricate patterns. Each photo comes with an at-a-glance guide that give the species' size, area of origin, and conservation status. Also included are habitat, life cycle and migration season. This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0387982418

ISBN13:9780387982410

Release Date:September 1997

Publisher:Springer

Length:234 Pages

Weight:1.30 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 6.4" x 9.5"

Customer Reviews

4 customer ratings | 4 reviews

There are currently no reviews. Be the first to review this work.