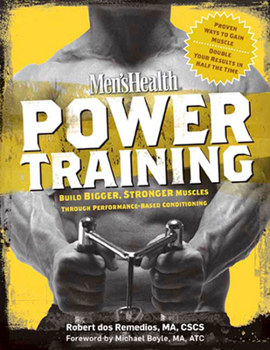

Men's Health Power Training: Build Bigger, Stronger Muscles with through Performance-based Conditioning

Select Format

Select Condition

You Might Also Enjoy

Book Overview

Customer Reviews

Rated 5 starsA book you should not be without!

There are three books in my workout library which I consider indispensable: Beyond Bodybuilding by Pavel Tsatsouline, Ultimate Flexibility by Sang H. Kim, and this book, Men's Health Power Training by Coach Dos. This book is outstanding in every way: explanations of power movements and why you should do them, illustrations, and examples of workouts for Hypertrophy, strength, and general fitness, as well as workouts you can...

0Report

Rated 5 starsA plan that works.

Here is a book that destroys the illusions surrounding weight lifting and strength training. Many of us sit in the gym wasting massive amounts of time on isolation exercises and judging our strength by bench press alone. This book focuses on total body fitness, compound exercises, balance from front to back, top to bottom. It emphasizes developing a powerful core and pure athleticism. I have placed my faith in this book and...

0Report

Rated 5 starssound practical advice..highly recommended

i really enjoy this book. in particular, the selection and variety of exercises is great. although beginners are encouraged to try, i would say it's best-suited toward people already in above-average shape or people at least 1-2 months into a regular workout program. many of the exercises suggested require a lot of proper technical form, balance, and maximal power, all of which could lead to serious injury without careful...

0Report

Rated 5 starsTraining with a program! Finally

I got this book from the library first but now it's on my Christmas list. This book is well worth the price! I'm sick of getting workout books that just show you a lot of the same old exercises and don't really give you a program or instruction on how to use the workouts. I believe that is why so many people are gravitating toward workout programs like crossfit, because they actually tell you what to do. I believe the problem...

0Report

Rated 5 starsthis book is changing my life

I'm 54 years old and have been lifting since I was 18. I've read countless weightlifting (mainly bodybuilding) books starting with Arnold's stuff in the 70's. I'm a physician. I've been exposed to very little of the material here, but as I understand it, much of it is used currently for athletic training such as football. This thing is packed with great material and I've been working at mastering some of the ideas for several...

0Report