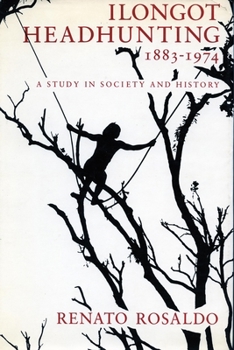

Ilongot Headhunting 1883-1974: A Study in Society and History

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

This study, a history of the kind of people who are supposed to have one, challenges the fashionable view that so-called primitives live in a timeless present. The conventional wisdom, that such societies are static, is shown by the author to be an artifact of anthropological method. By piecing together extended oral histories and written history records, the author found that headhunting among the Ilongots of Northern Luzon, Philippines, was not an unchanging ancient custom, but a cultural practice that has shifted dramatically over the course of the past century. Headhunting stopped, resumed, and stopped again; its victims at various periods were fellow Ilongots, Japanese soldiers, and lowland Christian Filipinos; it took place as surprise attack, planned vendetta, or distant raid against strangers.

Placing headhunting in its social, cultural, and historical contexts requires a novel sense of how to use biography, recorded history, and narrative in the analysis of small-scale, non-literate local communities. This study combines historical and ethnographic method and documents the inherent orchestration of structure, events, time, and consciousness. The book is illustrated with 34 photographs.