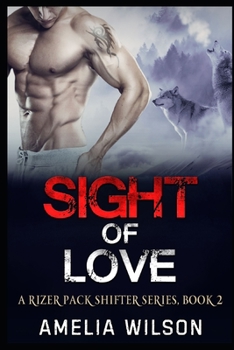

Vision d'amour: Romance paranormale

(Book #2 in the Rizer Pack Shifter Series)

What price is too high, if it means having visions of the future?

Angelina can see what most can't with her visions. She can't control her visions any more than she can control her physical response to Kilian, a shifter.

Kilian is tangled in her web of problems so fast he has no choice but to deal with the human woman, Angelina. He'd much rather be tangled in the sheets with the sexy, hot tempered, woman of secrets than her problems and knack for getting in trouble.

She's beautiful no question about it, but what Angelina will show Kilian will uncover a very dangerous path. It isn't a path Kilian can allow Angelina to travel alone.

Angelina can see what most can't with her visions. She can't control her visions any more than she can control her physical response to Kilian, a shifter.

Kilian is tangled in her web of problems so fast he has no choice but to deal with the human woman, Angelina. He'd much rather be tangled in the sheets with the sexy, hot tempered, woman of secrets than her problems and knack for getting in trouble.

She's beautiful no question about it, but what Angelina will show Kilian will uncover a very dangerous path. It isn't a path Kilian can allow Angelina to travel alone.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1091713324

ISBN13:9781091713321

Release Date:March 2019

Publisher:Independently Published

Length:122 Pages

Weight:0.42 lbs.

Dimensions:0.3" x 6.0" x 9.0"

You Might Also Enjoy

More by David Jackson

Customer Reviews

0 customer rating | 0 review

There are currently no reviews. Be the first to review this work.