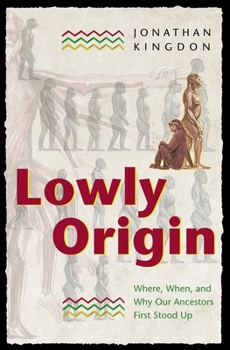

Lowly Origin: Where, When, and Why Our Ancestors First Stood Up

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Our ability to walk on two legs is not only a characteristic human trait but one of the things that made us human in the first place. Once our ancestors could walk on two legs, they began to do many of the things that apes cannot do: cross wide open spaces, manipulate complex tools, communicate with new signal systems, and light fires. Titled after the last two words of Darwin's Descent of Man and written by a leading scholar of human evolution, Lowly Origin is the first book to explain the sources and consequences of bipedalism to a broad audience. Along the way, it accounts for recent fossil discoveries that show us a still incomplete but much bushier family tree than most of us learned about in school. Jonathan Kingdon uses the very latest findings from ecology, biogeography, and paleontology to build a new and up-to-date account of how four-legged apes became two-legged hominins. He describes what it took to get up onto two legs as well as the protracted consequences of that step--some of which led straight to modern humans and others to very different bipeds. This allows him to make sense of recently unearthed evidence suggesting that no fewer than twenty species of humans and hominins have lived and become extinct. Following the evolution of two-legged creatures from our earliest lowly forebears to the present, Kingdon concludes with future options for the last surviving biped. A major new narrative of human evolution, Lowly Origin is the best available account of what it meant--and what it means--to walk on two feet.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0691050864

ISBN13:9780691050867

Release Date:April 2003

Publisher:Princeton University Press

Length:416 Pages

Weight:1.69 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 6.0" x 9.3"

Customer Reviews

2 ratings

Neotenous niche thieves rule!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

The next time you're tending your garden, pause a moment. Consider your position and local environment. Squatting down or on your knees, reaching around to weed or till, you are likely repeating a similar pose held by your ancient ancestors. According to Jonathan Kingdon, our African forebears started along their evolutionary path rooting about on the woodland floor seeking dinner. When conditions changed, they stood up to seek better places. The result was a questing ape that ultimately filled nearly every useful site on our planet. It will take serious research, an analytical mind and top-notch writing skills to surpass or supplant this superb study. Some artistic skills wouldn't go amiss, either. Kingdon has produced the finest work on human evolution since Darwin's Descent of Man. His focus is our upright stance, but he examines far more than simply physiology in explaining how we expanded around the globe. The story of human evolution was upended by Raymond Dart in 1924. Before then, as Kingdon relates, it was believed pre-humans grew large, useful brains before descending from the trees. Dart's Taung Child demonstrated upright walking developed long before our mighty minds. Why this was so is a question that has plagued anthropologists for decades. Kingdon lists thirteen theories for why we stood upright - then demolishes them thoroughly. He also peels away the idea that there's a clearly traceable lineage of successive steps from early hominins to modern humans. For one thing, he reminds us, fossil location doesn't necessarily reflect points of origin. The key word in Kingdon's title is not "how", but "why". Each species is adapted to its current environmental condition. Walking implies relocation and he posits that an East African "ground ape" likely followed rivers to their origins and beyond in the quest for resources. At some point, pre-human species became "niche thieves" - occupying or invading empty or inhabited resource areas. Vagaries of climate, the onset of disease or direct competition led to further changes in our physiology. We got better at walking, but we also learned new habits or improved on old ones. Twigs used to probe for food led to sticks for defence or attack, ending in spears for hunting. Spear casting is practiced from an early age in hunter-gatherer societies - young boys develop hunting skills through play activities. The retention of child-like traits is called "neoteny". Although this term is usually applied to body forms, especially facial features, it may also refer to behaviour. To Kingdon, childhood skills encouraged brain development to make us better hunters. Unfortunately, while granting us more complex reasoning ability, brain enlargement and ingenuity granted us access to a widening zone of niches without giving us insight into the impact of that exploitation. It has also led to humans setting themselves apart from the remainder of the animal kingdom. That fallacy, he

Get in touch with our ancestors

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

I recommend this book to anyone wanting to better understand our ancestors, not as unearthed fossils, but as living creatures who roamed the earth. Kingdon uses his own illustrations to bring us face-to-face with these ancient creatures, and to show just how we arrived on the scene. I am a scientist, but not an anthropologist, and have to admit that I needed to read the book twice to really understand it. Kingdon does not hand the reader easy answers, and does not provide summaries -- but rather proposes scenarios and dynamics that played out over several million years. This book is a delight, but it requires patience and/or some rereading.