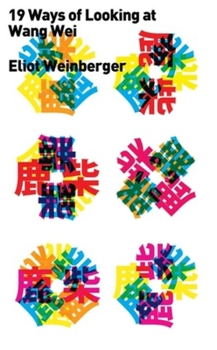

Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The difficulty (and necessity) of translation is concisely described in Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei, a close reading of different translations of a single poem from the Tang Dynasty--from a transliteration to Kenneth Rexroth's loose interpretation. As Octavio Paz writes in the afterword, "Eliot Weinberger's commentary on the successive translations of Wang Wei's little poem illustrates, with succinct clarity, not only the evolution of the art of translation in the modern period but at the same time the changes in poetic sensibility."

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0811226204

ISBN13:9780811226202

Release Date:October 2016

Publisher:New Directions Publishing Corporation

Length:64 Pages

Weight:0.24 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 4.4" x 7.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

The Impossible

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

The question inevitably arises when you are reading translations of poems from long ago from very different cultures - does this bear any resemblance at all to the poet's intent? Apart from the obvious practical difficulties, there is a vast difference in subconscious cultural assumptions. Why would someone write something down at all? It has something to do with the culture's beliefs about what matters and in that context what needs to be said. In the East, "emptiness" had a significance it doesn't have here. I think it derives from a personal experience of inner hopelessness, a facing an abyss within when you realize you have nothing of your own, and that all your character traits and virtues are worthless tricks in the face of your ultimate fate. The only remedy is to turn to that which is above. In the poem discussed in this book, that is the sunlight that returns to a piece of moss, as it rakes through the woods at sunset. Anyway, this book is a rather fun romp through 19 attempts to bring Wang Wei's meditation to the West. My own inklings about the poem were best expressed in what Octavio Paz had to say about his own translation. Most of the rest are undermined with brief and very funny observations by Weinberger. I doubt very much that any translation is likely to do the poem justice. Our culture doesn't value the experience of silence enough. We're definitely not looking for revelations about what a moment of inner silence shows. The need for noise is too great, need for noise and need for praise. But I think that is what Wang Wei was meaning to state, silence reflected, and really there is nothing in Western poetry that I know of that makes a declaration like this with such exquisite simplicity.

Amazing wee book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

I checked the book out of the local library a couple of weeks ago and have not stopped reading it since. The library volume is due back, so I just purchased it. My only complaint is that the last poem is Gary Synder's from 1978. I would like to see Mr Weinberger reissue the volume with latter translations such as Arthur Sze or Sam Hamill. And if any one is looking for a most needed project, a translation of all of Wang Wei's Wang River poems.

Nothing is more difficult than simplicity

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Poetry, said Robert Frost, is what gets lost in translation.Poetry, says Eliot Weinberger in the introduction to this small volume, is that which is worth translating.Both, of course, are right. That is what I like about poetry. It tolerates different points of view, a multitude of interpretations. A poem, or its translation, is never 'right', it is always the expression of an individual reader's experience at a certain point in his or her life: "As no individual reader remains the same, each reading becomes a different - not just another - reading. The same poem cannot be read twice.""Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei: How a Chinese Poem is Translated" contains a simple four-line poem, over 1200 years old, written by Wang Wei (c. 700-761 AD), a man of Buddhist belief, known as a painter and calligrapher in his time. The book gives the original text in Chinese characters, a transliteration in the pinyin system, a character-by-character translation, 13 translations in English (written between 1919 and 1978), 2 translations in French, and one particularly beautiful translation in Spanish by Octavio Paz (1914-1998), the Mexican poet who received the 1990 Nobel Prize for literature. Paz has also added a six-page essay on his translation of the poem.Wang Wei's poems are fascinating in their apparent simplicity, their precision of observation, and their philosophical depth. The poem in question here is no exception. I would translate it as:Empty mountainsI see no onebut I hear echoesof someone's wordsevening sunlightshines into the deep forestand is reflectedon the green mosses aboveCompared to the translations of Burton Watson (1971), Octavio Paz (1974), and Gary Snyder (1978), this version has a number of flaws. My most flagrant sin is the use of a poetic first person, the "I", while the original poem merely implies an observer. The translation reflects what I found most intriguing in the original text. First of all, the movement of light and sound, in particular the reflection of light that mirrors the echo of sound earlier in the poem. Secondly, the conspicuous last word of the poem: "shang"; in Chinese it is a simple three-stroke character that today means 'above' (it is the same "shang" as in Shanghai ' the city's name means literally 'above the sea').This is a very simple poem. The simplicity is deceptive, though. What looks very natural, still wants to make a point. The point is that looking is just one thing, but being open to echoes and reflections is what really yields new and unexpected experiences. Wang Wei applies the "mirror" metaphor in a new way in his poem. This metaphor was very popular in Daoist and Buddhist literature, and says roughly that the mind of a wise person should be like a mirror, simply reflective and untainted by emotion. Wang Wei seems to have this metaphor in mind when he mentions echoes and reflections in his poem. A Buddhist or a Daoist, for that matter, would also recognize the principle of "Wu Wei" (non-action)

An Amazing Look At the Relative Human Mind

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

The multiple translations of Wang Wei's poem are a door into the incredible spectrum of human thinking. This small delicate poem and its translations show how culture, translation and individual thinking change a work of art. I found myself writing a "translation" of the poem to discover yet another prismatic dimension of this jewel of a poem.

For anyone with an interest in translations

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

This book takes a 4 line poem in Chinese, then looks at 19 translations of the poem and provides a commentary on what works, does not work, is added, is omitted ... for three of the translations - Octavio Paz, Gary Snyder and Francoise Cheng comments of the translator are also given. This is a wonderful case study on the art of translation.Outside the aspect of translation, the volume also gives the reader ample opportunity to become familiar with Wang Wei's poem and with its Buddhist content.