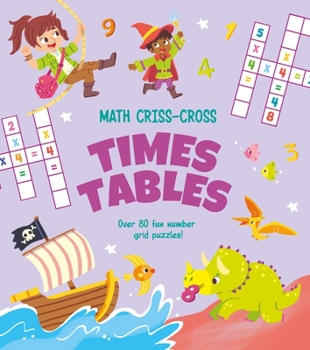

Math Criss-Cross Times Tables: Over 80 Fun Number Grid Puzzles!

Criss-cross puzzles are the new hit puzzle type. With interconnected grids, they provide a unique and inventive way for children to improve their math skills.

This vibrantly illustrated, ingeniously designed book transforms multiplication into a game that young readers will love. As they solve the puzzles, kids will be boosting the speed at which they can solve times table sums, and supercharging their mental math ability. It even includes a fun fact on every page, linked to the full-color illustrations. Providing invaluable screen-free time and endless entertainment, this activity book aims to bridge the gap between play and formal learning. Perfect for kids aged 6+.Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1398802611

ISBN13:9781398802612

Release Date:August 2021

Publisher:Arcturus Editions

Length:96 Pages

Weight:0.73 lbs.

Dimensions:0.3" x 9.2" x 10.2"

Age Range:6 to 10 years

Grade Range:Grades 1 to 5

You Might Also Enjoy

Customer Reviews

2 customer ratings | 2 reviews

There are currently no reviews. Be the first to review this work.