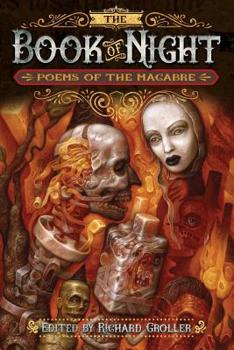

The Book of Night: Poems of The Macabre

Select Format

Select Condition

You Might Also Enjoy

Book Overview

Welcome to the world of shadows, cloaked in perpetual starlight; its denizens are a mysterious and frightening breed. And sometimes, just sometimes, their eldritch whispers and murmurs can cross the boundaries of reality and enter our darkest dreams.

Richard Groller and his troupe of dead and living poets pull back the veil in The Book of Night, revealing the terrifying denizens of the shadows. Eerie and hypnotic artwork by some of today's most chilling artists illuminates the vivid imaginings of the poets.

Apparitions-things seen and unseen at the edge of our vision, or embedded in the corners of our nightmares.

Sweet Sorrow-the pain and poignancy of loss, love unrequited, visions from afar, the pangs of memory, or the last breaths of mortals.

The Autumn People-denizens of the night welcome the Fall and its All Hallows promises.

Through A Glass Darkly-peer through the gloom seeking the moment of revelation, and all becomes clear-or not.

Come, the Night awaits...

Authors-Living:

Louis Agresta Larry Atchley, Jr. Jeff Barnes Dean M. Drinkel Richard D. Evans Jack William Finley Allan Gilbreath Richard Groller Michael Hanson Lori Martin Chris Morris Janet Morris Kurt Newton Jillian Perkins Kimberly Richardson Bill Snider Angel WeaverAuthors-Deceased:

Ambrose Bierce (1842-1913) Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) George Gordon (Lord) Byron (1788-1824) Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) Robert Frost (1874-1963) Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) William Ernest Henley (1849-1903) Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) Edward J.M.D. Plunkett, (Lord Dunsany) (1878-1957) Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)Artists:

Michael Bielaczyc Paul Bielaczyc Bob Giadrosich Liz Holland Chris Mars