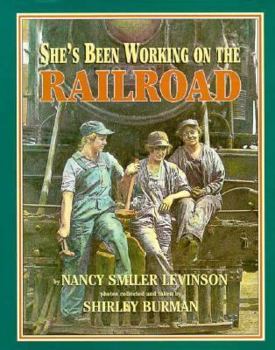

She's Been Working on the Railroad

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Women's unknown but important contribution working on the railroads is explored in this eye-opening account by award-winning author Nancy Smiler Levinson. She has written the book in collaboration... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0525675450

ISBN13:9780525675457

Release Date:October 1997

Publisher:Dutton Books for Young Readers

Length:96 Pages

Weight:0.99 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 7.4" x 9.3"

Age Range:10 years and up

Grade Range:Grade 5 and higher

Customer Reviews

2 ratings

Rosie the riveter

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

This 104-page six-chapter book is perfect for both children and adults wanting to learn about steam power, railroads and the women who worked on them during the two World Wars. We picked up our copy on a visit a few years ago to the U.S. steam railroad national park in Scranton, Pennsylvania. There a woman curator acted the part of Rosie, providing riveting details from the life of a World War II female railroad worker. The children loved it and insisted on getting this volume. The steam railroads began to take hold of the U.S. travel market in the 1930s, when people called them Iron Horses. The first three-page chapter describes the process by which trains replaced the horse and stagecoach and began to haul laws, raw materials and farm produce across the U.S. The railroads employed engineers, conductors, brakemen, firemen, station agents, dispatchers and many others to keep them running, not to mention the legions who worked to build thousands of miles of track. Most were men, but beginning in 1838, a handful of Native American and black women (the latter, freed slaves) began to work in domestic service jobs for the railroads. They also served water and sold fruit to women traveling in the ladies' cars. In 1855, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad hired Bridget Doheny, Catherine Shirley and Susan Morningstar as charwomen to clean the Camden, N.J. depot. In 1870, the Hartford & New Haven line hired a Mrs. T. Hatch to care for the Newington station for 75 cents a day. In the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s, women began working as telegraphers, known in the business as brass pounders. Women like Ella Campbell communicated by Morse code with brass telegraph keys, determining which trains had rights of way, often preventing accidents. Boiler explosions, blizzards, coupling cars and runaway trains caused accidents and deaths. But hundreds more would have occurred annually without the women who worked in train traffic control. Women also served as ticket sellers and train dispatchers. By 1900 they worked as clerks. Sarah Clark Kidder became the first woman president of a railroad in 1900 and Mary Pennington designed an improved refrigeration car and worked several years to convince railroad executives to use them. Mary Colter was an architect, who designed the Harvey chain of restaurants for the length of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa & Fe. Still others manned the chain as Harvey's girls. But the largest influx of women into the railroad workforces occurred during the two World Wars. With men recruited to fight in Europe, the U.S. labor market turned to women to fill their jobs. Thousands of women flooded key railroad jobs--as towermen, yardmasters, drawbridge tenders, steam-hammer and turntable operators, welders, brakemen, freight handlers--and riveters. During World War I, women worked a 48-hour week for as much as $95 a month, although they were often paid something less as "helpers." But they experienced strong patriotism and pride in their work, la

Will encourage young women to go into the "mans' world"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 26 years ago

I have experience in a lot of the fields mentioned in this book. The photographs and history behind them by Shirley Burman makes the women of yesteryear come alive again in my mind!! I thououghly enjoyed this book, and encourage others to read it. After 27 years on the railroad, there was a lot I learned from this book... Thanks, Shirley and Nancy.....!!!