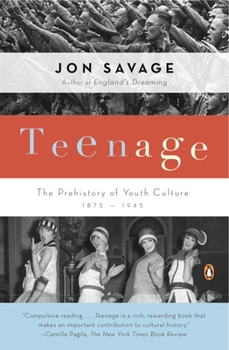

Teenage: The Prehistory of Youth Culture: 1875-1945

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In his previous landmark book on youth culture and teen angst, the award-winning England's Dreaming, Jon Savage presented the "definitive history of the English punk movement" (The New York Times). Now, in Teenage, he explores the secret prehistory of a phenomenon we thought we knew, in a monumental work of cultural investigative reporting. Beginning in 1875 and ending in 1945, when the term "teenage" became an integral part of popular culture, Savage draws widely on film, music, literature high and low, fashion, politics, and art and fuses popular culture and social history into a stunning chronicle of modern life.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0140254153

ISBN13:9780140254150

Release Date:March 2008

Publisher:Penguin Publishing Group

Length:576 Pages

Weight:1.18 lbs.

Dimensions:1.2" x 5.5" x 8.4"

Age Range:18 years and up

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

very educational

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

A very thick book. It is more interesting when you have some historical knowledge of the history. Full of lots of insights into the history of teenage culture.

the social history of youth culture

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Author Jon Savage is best noted for writing what many consider to be the definitive history of punk rock- "England's Dreaming" (personally, I prefer Greil Marcus's "Lipstick Traces".) In "Teenage"- his new book- he gets all ambitious. Teenage is a straight forward social history of what Savage calls "the creation of youth culture." One of the facts i learned this book, was that socialologist/philosopher Talcott Parsons coined the term "youth culture" in 1943. I think this book is a must read for professionals in the culture industries- journalists, music industry folks, etc. The 450 page length is a tad offputting, but the length is set off by the structure of the book: episodic, proceeding from the 1890s- to 1945 in chronological orders, most focusing on one specific youth cultures from the U.S., the U.K. or Germany (France is mostly absent, along with Italy, Austria and Spain). Generally speaking, Savage explicates his (fairly non-controversial) thesis that the industrial revolution stimulated the consciousness of youth as a class (by getting them into the work force early, creating more leisure time on a society wide basis, and weakening the relationship between children and their parents) and that "Youth" emerged in the mid 1920s as the most powerful "demographic" of western market capitalism. Not a very novel set of ideas- I think most would already "know" the above paragraph to be true at some innate level. The devil, of course, is in the details, and it is Savage's work with the primary sources of each particular era which elevates this work from tedious pop history to a must read classic. Working with the same careful eye for detail that marked his other work, Savage mines the detrius of low and middle brow culture (with the occasional shout out to contemporary academics and artists) with the skilled eye of a grizzled prospector. Savage starts off in the 1890s- the earliest chapters are the weakest. The apogee, as far as Savage is concerned is in the 20's: "The youth movement of the 1920s had been all too scucesful in creating their own discrete worlds. In doing so, they had reminded manufactuers, governments, and ideologues that youth comprised a social force that was far too important to be left to be left on its own." The next 10 chapters mainly deal with Hitler and his fondness for youth culture(!). Indeed, in Savage's analysis, Hitler's succesful appeal to youth was key in his rise to power within Germany. Hitler, it turns out was a fan of American advertising guru Bernays. Whether the goal is social control or consumer capitalism, the techniques, all too often, are the same. It's hard to read the Hitler Youth chapters without thinking a little bit about some of the common characteristics of youth culture. Specifically, the thought that youth, unburdened by experience- are quick to embrace extreme ideas and have little patience for ideas that invovle gradualness or delayed gratificiation. One of the intriguing inferences one

"Time to Murder and Create"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

This book is much more than a mere enquiry into the origins of youth culture - it is actually an absorbing historical account of what young people (in Western Europe and the USA) have experienced as the world underwent two big wars, a great economic crash, and several ideological experiments (from communism to fascism to "consumerism"). There seems to be an underlying question throughout Savage's quite detailed (and carefully researched) chronicle of youth from the mid-19th century to 1945: what happens when you have a) an economic system that needs to continually develop and expand in order to keep functioning (what we can summarize as "industrial society" or "capitalism"); and b) an oversupply of individuals who have to be organized in accordance with that system's necessities/aims (what we call "the mass")? The answer: you make youth, the most volatile and vigorous social cohort, instrumental - the pivotal point around which society defines (and renews) itself. Savage shows how from their organization around schools, factories and all kinds of diversions in times of peace, to their incorporation into armies in times of war, young people in industrial societies have been exposed to several more or less successful experiments in the complicated art of social management. Thus their energies were either channelled into productive and leisurely activities when the system of industrial production was focused on commercial expansion (developing a stunning variety of mass entertainments, fashion industries, etc) - or they were used as a violently destructive force when the system was concerned with geopolitical expansion (most clearly visible in WWI and WWII and colonialism). The main problem being that, malleable as a mass or group might seem, it often engages in pursuits that may not coincide with the industrial system's "best interests". Hence the history of the management of youth has been fraught with conflicts and clashes, as youth groups (sometimes of considerable sizes) challenged or outright rejected the roles society tried to impose on them: whether as workers/consumers or as soldiers. It is this problem which Savage addresses in his book, following youth's attempts to define itself as "independent" from adult society and its expectations, while simultaneously being exposed to ever more sophisticated laws and social measures determining its rights and obligations. Many of the most impressive cultural innovations came out of this friction. An interesting aspect in this conflict between young people and adult society is the generational rhetoric that became common after the French Revolution. Again and again, the "new generation" (or actually a loud minority in it) defines itself as radically different, even opposed to its predecessors, and announces a glorious future, when the young will finally take over and correct the mistakes of the past. Using countless examples (from the decadents and nihilists, through the "lost generation" and "brigh

Move Over, Your Replacements Have Arrived

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

The concept of teenagers as a group separate from children and adults is relatively new. It wasn't until World War II that the word existed and that was in response to advertisers who realized that young people had money to spend. But teenagers weren't invented during the 1940s. In writing the history of teenagers from Victorian times until World War II, author Jon Savage has shown that their history is our history. They don't govern nations or run companies, but they fight wars, earn money, commit crimes and when it comes to movies and music, it's teenagers who decide the trends. Savage defines teenage loosely, as being from about age twelve to mid-twenties. Teenagers aren't children anymore, but they don't have the responsibilities or the experience of adults. They are like adults who haven't mastered their emotional volume control yet. Their highs are higher and their lows are lower than adults who've learned to expect disappointments and are too self conscious to enjoy with abandon. Teenagers have their lives ahead of them and anything is possible. They have little to lose and can take risks that most adults wouldn't dare. Teenage is full of interesting stories of trend-setting teenagers such as Oscar Wilde and Arthur Rimbaud, but it's not until World War I that teenagers became really influential. With the invention of movies and radio, teenagers became the early-adopters of their times. Rudolph Valentino's fame and the reaction to his death and funeral remind me of the arrival of the Beatles in New York. Leopold and Loeb killed a child and thought they were too smart to get caught. When they were caught, they acted like celebrities during the trial, wearing stylish clothes and attracting an ardent following of young admirers. Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney were overwhelmed at first by their hysterical fans, but quickly adapted. Savage's study examines teenagers in the U.S., England, France, and Germany. We see the youth who followed the rules: the Boy Scouts and the Hitler Youth. We see the ones who rebeled: the Zoot Suiters and the White Rose, an anti-Hitler German group who came to a tragic end. The dilemmas of when to treat teenagers as adults and when to treat them as children have been around as long as teenagers have. When do you try a teenage criminal as an adult? At what age should young adults be allowed to drink alcohol? Get married? Join the military? Leave school? Earn a living? Leave home? There are no answers here, but it might help to realize that we aren't the first to ask the questions. And even if it doesn't help, Teenage is an excellent social history.

To be young again

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Back when I was a teen, we called our elders "sir" and "ma'am", practiced our penmanship, and sang patriotic songs whenever we got together with friends. Nowadays teens run roughshod without adult supervision, blast loud music from their "cars", and would just as soon glare at you as spit on the street, which they do often--that is, when they are not otherwise shopping, consuming mass media, or conforming to their market-researched ideas of themselves. Just where did this "teenage" culture come from? In earlier times, children passed either straight into adulthood or into some kind of supervised apprenticeship, learning a useful trade or craft, the vestiges of which can still be seen in family names like "Smith", "Farmer", "Clerk" and "Sweeper". Jon Savage attempts to trace the origins of adolescent culture, "adolescence" defined by G. Stanley Hall as a time of moodiness, risky behavior, and conflict with the previous generation--all things that a cold shower and self-flagellation could easily take care of--in his lively tome "Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture". Savage begins his tale at the end of the Victorian age, when youths in England and Germany were being molded for imperial service and youths in America were swelling in number from recent immigration. The destruction of so many young people in World War I led to disillusionment and the beginnings of U.S. cultural dominance, feeding the fun-loving, convention-defying Roaring Twenties and the Jazz Age. Here, Savage demonstrates his strength in describing the music, idols and popular culture of the era, a culture that was increasingly catering to youth and the ideal of youth. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Mussolini and Hitler both catered to and exploited the idealism and innocence of the young. In counterpoint, Savage retells the story of Anne Frank to chilling effect. The narrative unfortunately ends in the mid 1940's, anticipating the next post-war rise of youth in the counterculture of the 1960's. What Savage does present, however, is a rich and vibrant recounting of the many cultural facets that fed and amplified the energy, discontent, optimism and joy of youth, something I wish I could get back by sucking it out of the youth of today.