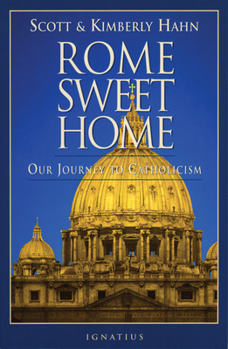

Rome Sweet Home

Select Format

Select Condition

You Might Also Enjoy

Book Overview

Scott Hahn was a Presbyterian minister, the top student in his seminary class, a brilliant Scripture scholar, and militantly anti-Catholic ... until he reluctantly began to discover that his enemy had all the right answers. Kimberly, also a top-notch theology student in the seminary, is the daughter of a well-known Protestant minister, and went through a tremendous dark night of the soul after Scott converted to Catholicism.

Their conversion story and love for the Church has captured the hearts and minds of thousands of lukewarm Catholics and brought them back into an active participation in the Church. They have also influenced countless conversions to Catholicism among their friends and others who have heard their powerful testimony.

Written with simplicity, charity, grace and wit, the Hahns' deep love and knowledge of Christ and of Scripture is evident and contagious throughout their story. Their love of truth and of neighbor is equally evident, and their theological focus on the great importance of the family, both biological and spiritual, will be a source of inspiration for all readers.