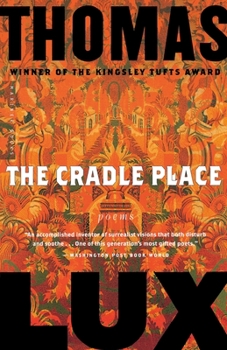

The Cradle Place: Poems

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The Cradle Place is a collection from Thomas Lux, a self-described "recovering surrealist" and winner of the Kingsley Tufts Award. These fifty-two poems bring to full life the "refreshing iconoclasms" Rita Dove so admired in Lux's earlier work. His voice is plainspoken but moody, humorous and edgy, and ever surprising. These are philosophical poems that ask questions about language and intention, about the sometimes untidy connections between the human and natural worlds. In the poem "Terminal Lake," Lux undermines notions of benign nature, finding dark currents beneath the surface: "it's a huge black coin, / it's as if the real lake is drained / and this lake is the drain: gaping, language- / less, suck- and sinkhole." In the ominous "Render, Render," the narrator asks us to consider a concentration of the essences of our lives: all that is physical, spiritual, remembered, and dreamed for, melded together to make the messy self we present to the world. Lux's voice is intelligent without being bookish, urgent and unrelentingly evocative. He has long been a strong advocate for the relevance of poetry in American culture. The Los Angeles Times praises Lux for his "compelling rhythms, his biting irony, and his steady devotion to a craft that often seems thankless." As Sven Birkerts noted, "Lux may be one of the poets on whom the future of the genre depends."

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0618619445

ISBN13:9780618619443

Release Date:August 2007

Publisher:Houghton Mifflin

Length:80 Pages

Weight:1.30 lbs.

Dimensions:0.2" x 5.5" x 8.3"

Related Subjects

PoetryCustomer Reviews

2 ratings

4-star review for a 5-star poet

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

I am a big fan of Thomas Lux's work--when his work is sharp, he thrusts you immediately into a new quantum universe which is sometimes familiar, or sometimes not. Either way, it quickly establishes its own rules and explores those rules to some human conclusion. Poems of his like "Wife Hits Moose" or "Baby, Still Crying, Swallowed by A Snake" quickly explore the new territory they have established to finally make some point about faith or hopelessness. Unfortunately, the poems that I just named are not ones that appear in this particular collection. I am always glad to see a new collection by Lux, for I know that the situations of his poems are going to continually surprise me, whether they are horses who die mid-gallop or mummies about to be ground into powder for other uses. But a few poems in here fail to reach those human conclusions that really mark Lux's best work. At one point, we find the speaker of a poem chastising himself for the kind of historical obsession Lux himself has shown in his poems, but this conclusion is unsatisfying and seems almost the work of a novice, which Lux is not. A marvellous poem in this collection is "To Help the Monkey Cross the River," which in the end produces a hypothetical choice as wise and as wide as implication as Ginger or MaryAnn?, or Steak or Shrimp? This poem is a fine example of the pure genius of Lux, but these examples are more scant in this book. I still look forward to the next Lux collection but am not fully satisfied with this particular production.

Primordial milk

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Most of what I can say about *The Cradle Place* will sound too much like what I said about *Street of Clocks*, but it's still true: this is one good poet, and this is another good book. If you haven't read Lux before, go look at *The Street of Clocks* for my sprawling encomia on the Lux oeuvre. Specific and concrete of detail, distinctive and musical of voice, celebratory and humorous and really funny: all of the above still apply.So how (I hear you cry) is *The Cradle Place* different? Well, I think I'm detecting an increasing trend toward what I'd call allegory if "allegory" weren't so unfashionable a term at the moment. "Professor of Ants", "Asafetida", "The American Fancy Rat and Mouse Association"-these have pretty clear more-than-metaphorical implications. And I see, or imagine I see, a deepening dark streak, more of a "gletz", if you like: that "breathless, cell-sized cell/where two inmates are locked/and each has a knife." Of course, calling Lux's poems dark at this late date may sound funny, considering that the author was writing about leech farming seven or eight years back; but when my husband prised my head out of the book to ask how it was looking, my first-blush response was "these are not happy poems." In retrospect some of them seem more so--the final poem, which already made my day when it appeared in APR, is very lively, and it's good to think that out of the magma chambers the heart spews into the world we can make "a new republic of hope." But we are seeing, this time, a can of alphabet soup full of "little noodle swastikas" (if I'd been planning to ever eat alphabet soup again, I wouldn't be now.) The birds here are nailed to trees in museums, waiting to be picked off by mummified boys with pellet guns. The poet acknowledges that if we value our necks, there are times when we'll "shut the f--- up", that our bones are owned by something else, and that he wants to "whack-smack" the One Afraid to Be Seen. And call me a sentimental putz, but I hate it when even my favorite authors behead bees, ironically or no, and the Dobyns-esque worldview that might see the bee as having no existence outside of perception and allegory and words doesn't exactly warm the cockles of my hard but animistic heart. So, yeah, there are indeed "Scorpions Everywhere" here. One of the epigraphs is Roethke's cry for "the old rage, the lash of primordial milk", and I expect it's here. Still, I think you, gentle Reader, should read the book. After all, there are a whole lot of scorpions out there (albeit probably not masquerading as squirrels), and it doesn't make the world any worse to look at them, and plant even on them "as many kisses as the world will bear."