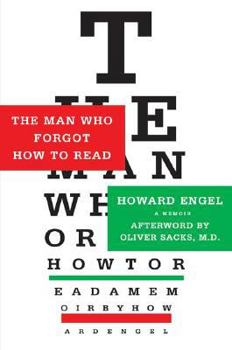

The Man Who Forgot How to Read

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The remarkable journey of an award-winning writer struck with a rare and devastating affliction that prevented him from reading even his own writing One hot midsummer morning, novelist Howard Engel picked up his newspaper from his front step and discovered he could no longer read it. The letters had mysteriously jumbled themselves into something that looked like Cyrillic one moment and Korean the next. While he slept, Engel had experienced a stroke and now suffered from a rare condition called alexia sine agraphia, meaning that while he could still write, he could no longer read. ??????????? Over the next several weeks in hospital and in rehabilitation, Engel discovered that much more was affected than his ability to read. His memory failed him, and even the names of old friends escaped his tongue. At first geography eluded him: he would know that two streets met somewhere in the city, but he couldn't imagine where. Apples and grapefruit now looked the same. When he returned home, he had trouble remembering where things went and would routinely ?nd cans of tuna in the dishwasher and jars of pencils in the freezer. ?????????? Despite his disabilities, Engel prepared to face his dilemma. He contacted renowned neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks for advice and visited him in New York City, forging a lasting friendship. He?bravely learned to read again. And in the face of tremendous obstacles, he triumphed in writing?a new?novel. ??????????? An absorbing and uplifting story, filled with sly wit and candid insights, The Man Who Forgot How to Read will appeal to anyone fascinated by the mysteries of the mind, on and off the page.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:031238209X

ISBN13:9780312382094

Release Date:July 2008

Publisher:Thomas Dunne Books

Length:157 Pages

Weight:3.03 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 5.9" x 8.4"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

The Man Who Forgot How to Read

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

In January, my husband had a stroke which left him with Alexia. The author's experience gives us hope that he, too, will recover his ability to read. The biggest problem is finding therapists who are trained to help.

Coping with Catastrophy

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Howard Engel woke up one morning, opened his daily paper and discovered he could no longer read. "The letters, I could tell, were the familiar twenty-six I had grown up with. Only now, when I brought them into focus, they looked like Cyrillic one moment and Korean the next." He had had a stroke. As the morning proceeded he forgot names - including his own. Familiar landmarks appeared in unfamiliar places. He was unable to say what relation he was to his son. While all this would be devastating to anyone, the alexia - his inability to decipher written words - was a special blow. Engel was not only a voracious reader, he was a writer, the award-winning Canadian author of the popular Benny Cooperman detective series. He had lost his means for making a living. Or maybe not. Engel had alexia sine agraphia. Which meant he could still write - he just couldn't read what he had written. "The sine agraphia was the sop designed to make me feel good. It was like being told that the right leg had to be amputated but that I could keep the shoe and sock." But the possibility continued to percolate as he went through weeks of rehab and readjustment. Engel relates this time of confusion and effort with humor, clarity and insight, exploring the mysteries of the brain and its elastic abilities to compensate and fill in gaps. Back at home, while still putting garbage in the dishwasher or laundry in the fridge, a book begins to take shape. Benny, his detective, hospitalized with brain damage after a blow to the head, solves the mystery of how it happened without leaving his hospital ward. Engle describes the strangeness of composing a chapter and being unable to read it; of starting down a plot path and forgetting its destination, of the tricks he uses to anchor himself to the text. Spare, thoughtful and upbeat, Engel illuminates the "insult" to the brain and the business of learning to live with it. He had help - a wide network of family and friends and a relationship with neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks, who provided an afterword for Engel's post-stroke Cooperman book and supplies another for this memoir. But it was his own calm acceptance and determination that got him through each day and will arouse empathy and admiration in the reader.

RICK "SHAQ" GOLDSTEIN SAYS: "THE AUTHOR & I HAVE KNOWLEDGE BY EXPERIENCE, AND NO KNOWLEDGE BY DESC

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Five-and-one-half years ago I almost died during brain tumor surgery. Going into brain surgery, you would think that my fear of dying was my biggest fear... but it wasn't! I told my son Justin that I wasn't afraid of dying, because I know I raised him correctly, and he became the man he is today... and being the man he became, I was prouder of him than anything I had ever done in my entire life... so I knew he would be ready to carry on. I also was able to say goodbye to him the way I wanted to, as the second's ticked away leading to my surgery. A lot of people watch too many movies, so they think everybody gets to be like John Wayne... and get to give a big emotional speech as they die in someone's arms. My absolute biggest fear... which I told my son, and my brain surgeon... is becoming a "vegetable"... or having this super-fast brain I was blessed with... locked in a body... and not be able to communicate. I made my son promise to tell me the truth, and not lie to me after the surgery, if I made it through, and couldn't repeat certain key statistics to him such as all fourteen Major League ballplayer's who won the triple crown. I survived the surgery (I wasn't told for three weeks about what really happened during the surgery.) despite some unexpected developments, including bleeding in the brain, which occurred during the surgery. When I was allowed to go home, I didn't know what Jello was... I didn't know what a lamp or dresser were... I didn't know what a bagel was. And probably the most heart-wrenching memory "shortcoming" was that periodically I knew who Justin was... but I couldn't remember that he was my son. It was the most frightening thing I had ever experienced... and remember I just went through major brain surgery. I had always felt such empathy for the poor human beings that suffered from the ever growing curse of Alzheimer's disease. Many people wonder, "What does that feel like?" Here's the best way I can explain it to you from firsthand knowledge: IT'S LIKE OPENING UP A FILE CABINET DRAWER TO GET SOME INFORMATION THAT'S IN A FILE FOLDER. YOU KNOW THE FILE FOLDER IS IN THERE... BUT THE DRAWER IS TWELVE INCHES DEEP... AND YOU CAN ONLY REACH IN TEN INCHES. IT DOESN'T MATTER HOW HARD YOU REACH... IT DOESN'T MATTER HOW HARD YOU STRETCH... YOU CANNOT REACH IT! That's what it feels like, when your brain no longer automatically gives you information you know you have... but can't get at. The author, Canadian writer Howard Engel, is the creator of "the beloved detective Benny Cooperman series." Howard did not have to count down the hours and minutes to brain surgery... he simply went to bed one night... woke up on July 31,2001, went to the front door to pickup his newspaper, "and it looked the way it always did in its make-up, pictures, assorted headlines and smaller captions. The only difference was that he could no longer read what they said. The letters looked like Cyrillic one moment and Korean the next. Where he could make out

"It was plain that I was no longer playing with fifty-two cards."

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Seventy-seven year old Howard Engel, who lives in Toronto, Canada, has been a "reading junkie" since he was a little boy. He is the creator of fictional private investigator Benny Cooperman, the hero of "more than a dozen novels, several short stories, radio broadcasts and two films." Engel wrote almost a book a year for over two decades and in the mid-eighties, he quit his job at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation to devote himself to full-time writing. One morning in July, 2001, the author suffered a stroke that robbed him of his ability to read. This memoir describes the author's struggle to regain his literacy, assisted by "a small army of people who helped [him] climb all those steps." When he had his stroke, Engel was seventy years old, a success in his chosen field, widowed, and the father of a twelve-year-old boy. For some reason, Engel did not panic when he realized that the letters in his local newspaper did not appear to be in English. "They looked like Cyrillic one moment and Korean the next." He bundled up his son, Jacob, and called a cab to take them to the hospital. He soon learned the name of his condition: alexia sine agraphia, "word-blindness" or the inability to recognize printed symbols without losing the capacity to write. Ironically, Howard could not decipher the words that he put down on paper. His stroke had damaged his occipital cortex on the left side. He also lost a quarter of his vision "in the upper right hand side of the visual screen." "The Man Who Forgot How to Read" is Engel's mostly upbeat recollection of his brief time in Mount Sinai Hospital, his stay in the Toronto Rehabilitation Hospital, and his return home. His account is dryly humorous, poignant, and remarkably devoid of self-pity. He realized that he was lucky not to be paralyzed or stricken with aphasia, a general disturbance of language that would have been even more devastating. Although he was often confused and suffered from persistent memory loss, Engel was able to communicate freely with his many visitors. He was also extremely fortunate to have a network of relatives and friends who took care of Jacob and managed the Engel household while Howard was recuperating. Engel learned to compensate for his faulty memory by using mnemonic devices, such as associating someone with a famous person from literature. He remembered the name of one of his favorite nurses, Kathy, by linking her in his mind with Catherine, Heathcliff's great love in "Wuthering Heights." He also became friendly with his fellow stroke victims; chatting with them cheered him up and helped pass the time. The patients tried to buoy one another's spirits in whatever ways they could. Trips to the gym, writing notes down in his "memory book," and a team of social workers also facilitated his recovery. He worked with a reading specialist, a speech-language pathologist, and other experts who helped him salvage as much of the old Howard as he could. This is a hear