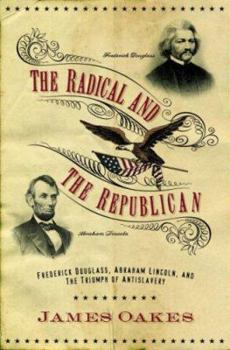

The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The frontier lawyer and the former slave, the cautious politician and the fiery reformer, the president and the most famous black man in America - their lives met in the bloody landscape of secession, civil war and emancipation. Opponents at first, Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln gradually became allies, each influenced by and attracted to the other. James Oakes brings these two iconic figures to life and sheds new light on the central issues of slavery, race and equality in Civil War America.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0393061949

ISBN13:9780393061949

Release Date:January 2007

Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

Length:328 Pages

Weight:1.15 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 5.8" x 8.5"

Related Subjects

Abolition Africa African-American & Black African-American Studies Civil War Discrimination & Racism Ethnic & National History Military Modern (16th-21st Centuries) Political Science Politics & Social Sciences Race Relations Social Science Social Sciences Specific Demographics United States Civil War WorldCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

A refreshing, challenging, stimulating, thought-provoking look at both men

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

On Douglass, Oakes looks at how he moved from radical to politician throughout his life, including wedding himself so much to the GOP in his last years that he apparently never entertained the idea of a "Free Vote Party" paralleling the Liberty Party of his younger days. No, it's not a full bio, but it leads to further questions. Was this the "settling" of an old man? Was it an evolving pragmatism? Did getting a patronage job bank his inner fires? On Lincoln, Oakes takes a careful look at the long-debated issue as to whether or not he had any racist bones, either before election to the presidency or even after. On 126-29, Oakes tackles the pre-1860 politics of Lincoln re black-white relations beyond slavery with depth. He says Lincoln simply accepted white intransigence was so great that blacks never could have equality and that it was not a case of Lincoln himself rejecting racial equality. Nonetheless, Oakes believes "spineless" is a legitimate charge, as is "cynical." More serious are some of the themes from a pro-colonization lecture, in essence, Lincoln gave to northern black leaders shortly before announcing the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Oakes sees this as a more cynical version of Lincoln's 1850 stance on accepting white racism even though Lincoln didn't hold to it himself. After claiming in the past "racism" and "slavery" were different, Oakes says Lincoln now tried to conflate them with a cheap syllogism. This level of analysis is what makes the book all of the things I said in my header. No, again, this is not a complete dual bio. But Oakes' excellent "For Further Reading" appendix points to the best bios on both men, as well as takes on the Civil War militarily and socially, Reconstruction and more.

Puts the radical ideologist and the political realist in historical perspective

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

One of the easiest things to do, especially on the web, is to take a highly regarded leader of the past, say, Abraham Lincoln, pull a few of his quotes or actions out of their historical context, and supposedly "prove" how horrible that leader actually was. In contrast, author James Oakes explains Lincoln to us postmoderns the way an historian should - by reminding us of Lincoln's circumstances and explaining Lincoln's overarching purposes. Oakes does this without resorting to making Lincoln a saint. According to Oakes' compellingly-supported evidence, Lincoln refused to compromise two essential commitments - to antislavery and to the American political system. Lincoln would not compromise his antislavery position to get more votes, nor would he compromise his oaths to uphold the Constitution to undermine slavery. This dual commitment of Lincoln's goes very far in helping us understand why Lincoln limited his goal to preventing the spread of slavery before he became president, why he didn't just go ahead and free all the slaves when he became president, why he moved slowly towards emancipation during the war, etc. Furthermore, the author's discussion of Lincoln's overwhelming desire to change the hearts and minds of Americans about slavery instead of merely forcing through political change regardless of wider support was especially useful. As the "Republican" in the title, Lincoln wanted a government that represented the will of the people; therefore, the will of the people needed to be converted before the government could make radical change. The fact that Lincoln helped accomplish this more widespread change is quite a testament to his legacy of leadership. The "Radical" in the title is another great American, Frederick Douglass. Unlike Lincoln's, Douglass' reputation typically is not in dispute. Most of us love Douglass, and for good reason. Oakes doesn't tarnish Douglass' reputation, but he does help us to understand how Douglass' singular commitment to antislavery/antiracism, as compared to Lincoln's dual commitment explained above, often put Douglass at odds with the political process AND caused Douglass to speak out so vehemently against politicians like Lincoln. From Douglass' perspective, only immediate emancipation and egalitarianism would serve justice. Thus, by necessity, Douglass would oppose and criticize Lincoln - that is, until the two men met. One of the reviewers below critiques Oakes for supposedly overstating the relationship between the two men. I believe this critique is misplaced because Oakes never claimed to be writing primarily about the interpersonal relationship between the two. Instead, he's writing about the interplay of the radical ideology of one, and the antislavery politics of the other. Also, I think that Oakes analyzes the relationship between Brown and Douglass comprehensively, not simplistically, as a reviewer below seems to believe. As a person who teaches hi

What changed Frederick Douglass' mind

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Author James Oakes tells us this: in 1860 Frederick Douglass wrote of the upcoming presidential election "I cannot support Lincoln." But in 1888, Douglass said he had met no man "possessing a more godlike nature than did Abraham Lincoln." What had happened? Oakes gives us a quick glance at his hypothesis within the subtitle of his book: the triumph of antislavery politics. As he explains, this doesn't apply to Lincoln. Lincoln was always an anti-slavery politician, although his thinking on how and how fast slavery should be destroyed changed over time. But with regards to the use of politics as the means to abolish slavery, the man whose thinking moved more was Frederick Douglass. And although the two men share the billing in Oakes' title, this is far more a book about Douglass than Lincoln. It is a book about the evolution of the reasoning of Frederick Douglass. That evolution, as Oakes paints it, began for Douglass from the belief that the issue of slavery transcended politics and the compromises that came with it. Oakes traces how Douglass the reformer began to be drawn into the political arena, alienating the abolitionists who had first supported his career. But still he carried with him that insistence on absolutism. He brooked no delays, no strategic maneuverings. Lincoln and the Republicans were gradualists, and therefore were deemed irresolute and untrustworthy. After the Civil War began, Douglass found even more reasons for outrage. Lincoln refused to immediately emancipate the slaves. The President even countermanded the Union generals who issued proclamations freeing the slaves in the territories they conquered. Lincoln had not yet issued a retaliation policy against confederates who captured and often executed southern blacks who had joined the Union army. Oakes gives us deft insights into Lincoln's thinking on all these issues. Douglass, who apparently was not himself an acolyte of consistency, bounced back and forth in his electoral attitudes. But he never let up in his pressure on Lincoln nor in his condemnation of the President's lack of strong steps against slave-holding interests. Then, first in 1863, Lincoln meets with Douglass. About a year later, at Lincoln's request, they meet a second time and Lincoln asks Douglass to draw up a plan to get as many slaves freed under the Emancipation Proclamation as possible. Over that span Douglass' thinking with regards to Lincoln undergoes a dramatic shift. Afterwards, his criticism of Lincoln essentially stops. Oakes describes these meetings, including a third just after Lincoln's second inaugural address, in as much detail as consistent with the small format of the book. He relies largely on Douglass' own recollections. Oakes also gives us dramatic retellings of other events in Douglass' career that illustrate the development of his thinking, but also the refinement of his skills as a political strategist. We are still left wondering what exactly was the effect of those meeting

The Politician and the Reformer

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Abraham Lincoln (1809 --1865) and Frederick Douglass (1818 -- 1895)are American heroes with each exemplifying a unique aspect of the American spirit. In his recent study, "The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics" (2007), Professor James Oakes traces the intersecting careers of both men, pointing out their initial differences and how their goals and visions ultimately converged. Oakes is Graduate School Humanities Professor and Professor of History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He has written extensively on the history of slavery in the Old South. Oakes reminds the reader of how much Lincoln and Douglass originally shared. Lincoln and Douglass were self-made, self-educated, and ambitious, and each rose to success from humble backgrounds. Douglass, of course, was an escaped slave. Douglass certainly and Lincoln most likely detested slavery from his youngest days. But Lincoln from his young manhood was a consummate politican devoted to compromise, consensus-building, moderation and indirection. Douglass was a reformer who spoke and wrote eloquently and with passion for the abolition of slavery and for equal rights for African Americans. Much of Oakes's book explores the difficult subject of Lincoln's attitude towards civil rights -- as opposed simply to the ending of slavery -- and of how Lincoln's views developed during the Civil War. Oakes uses Douglass as a foil for Lincoln beginning with the Lincoln -- Stephen Douglas debates in Illinois in 1858. Steven Douglas tried hard to link Lincoln to Frederick Douglass and to abolitionism. He claimed that Lincoln favored equal rights for Negroes and raised the spectre of intermarriage between white women and black men. Portions of Lincoln's responses to Stephen Douglas were almost as distressing, as Lincoln carefully avoided supporting civil equality between the races and stressed instead the evil of slavery and the need to stop its expansion. It is not surprising that Douglass the abolitionist was ambivalent and mistrustful of Lincoln in the early years, doubting his committment to the cause of ending slavery. Douglass continued to distrust President Lincoln. Douglass found the President too quick to temporize and too slow to act towards freeing the slaves. In widely publicized actions, Lincoln had rebuked two of his generals, Freemont and Hunter, who had tried to take aggressive action to free slaves. Lincoln had acted in order to keep on good terms with the border states whose support he deemed necessary to a successful war effort. But Douglass saw Lincoln's actions as weak and waffling. Douglass's attitude gradually changed with the Emancipation Proclamation and with three meetings between the two men in 1863, 1864, and 1865. Douglass was won over by the President. Lincoln, for his part, seemed to view Douglass with genuine affection and friendship. Douglass gave masterful orations s

Neglected History

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

I enjoyed this book because it showed the civil rights struggle with all its complexities in a very clear and understandable way. The interaction of Douglas and Lincoln was especially interesting because it provided a very human picture of good men trying to deal with the thinking and forces operating during that time.