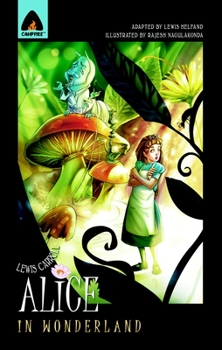

Alice In Wonderland

Select Format

Select Condition

You Might Also Enjoy

Book Overview

Alice was just an ordinary girl - imaginative and curious and thirsting for adventure. She was an ordinary girl, that is, until she found herself instantly transported to a place that was anything but ordinary. After diving down a rabbit hole, young Alice encounters a magical world ruled by a vicious Queen. It is a world where anything can happen; a world filled with a talking caterpillar, a puppy as big as a house, and a Cheshire cat that can disappear and reappear in the blink of an eye. Are these colorful characters real? And if so, how will Alice ever find her way back home?

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:9380028237

ISBN13:9789380028231

Release Date:July 2010

Publisher:Campfire

Length:72 Pages

Weight:1.80 lbs.

Dimensions:0.1" x 6.6" x 10.2"

Age Range:8 to 11 years

Grade Range:Grades 3 to 6

More by Robert Williamson

Customer Reviews

1 customer rating | 1 review

Rated 4 starsNature and sibiling rivalry combine for a hard to put dow

By Thriftbooks.com User,

This book is compelling in its magnetic description of the harshness and beauty of the Alaskan wilderness. It poses tough questions to its intended middle-school audience . Josh is more comfortable with the amenities of the modern world and his half brother Nathan , who favors himself as a modern - day Thoreau , are in constant conflict.Their father seems powerless to resolve his own or their problems . The story has adventure...

0Report